Halfway through my first year of middle school, Janet was making a point of noting whether our names were on one of two lists called Honor Roll and Honorable Mention. I had never heard of these lists and didn’t know what it meant to be on one of them. “It has to do with your grades,” she told me. If you got almost all A’s, you got on Honor Roll. I had made Honorable Mention.

This was a new concept to me. No one had ever made much comment about my grades, so it seemed strange to realize that this mattered. I did remember Pete catching holy hell one time, back when we lived in Barron, for getting a bad grade on a test or in a class. Given the decibel level of my mother’s yelling, he must have gotten a D or an F. But I never heard a peep aimed towards me.

Actually, I have an odd little story stuck in the back of my mind. I don’t know who told me this—maybe Jeff?—and I don’t how true it is. It goes like this: When I was very young, like first or second grade, they gave some kind of IQ test and our neighbor, who was a janitor at the school, saw my score. He told my parents about it and they decided this was a piece of information I should not be told: I was smart.

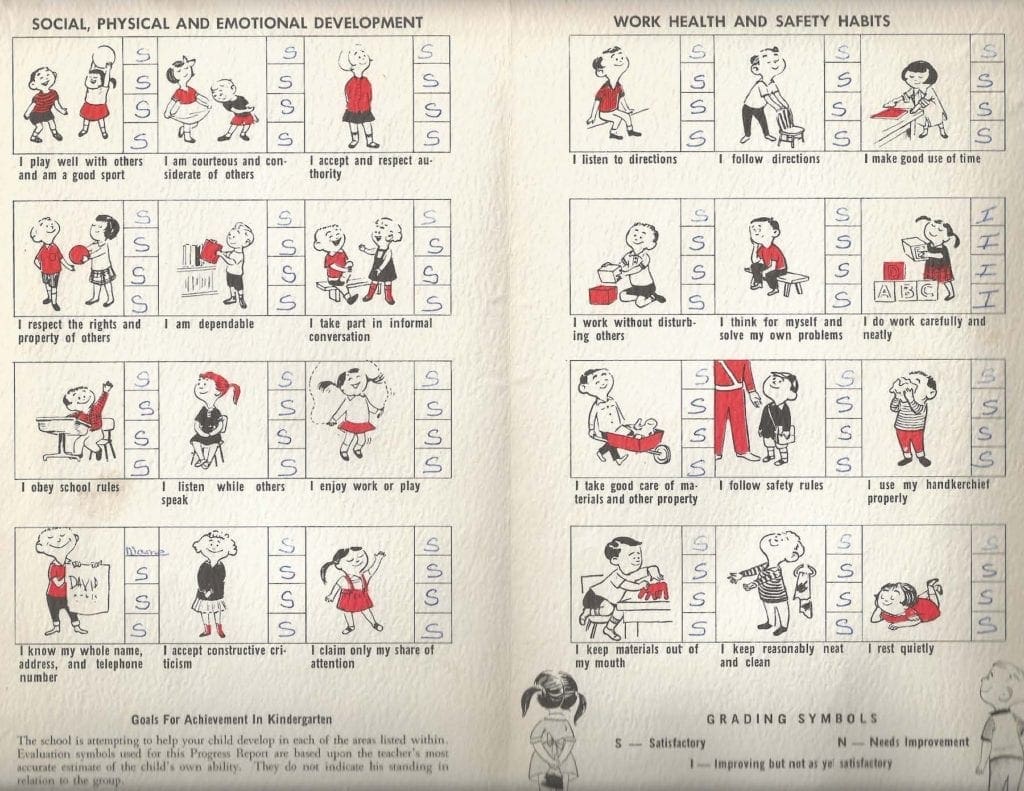

In fact, when I was in early grade school, they were trying out a new system in which students didn’t get grades. Of course, in kindergarten it was just S, N or I anyways, for Satisfactory or Need Improvement or Improving But Not as Yet Satisfactory. Mostly, I was a straight-S student but dropped the ball on working carefully and neatly, proving that people really can change.

Well, life falls forward and now here I was in sixth grade, realizing for the first time that someone was paying attention to more than attitude. They noticed your grades! So I started to pay attention as well.

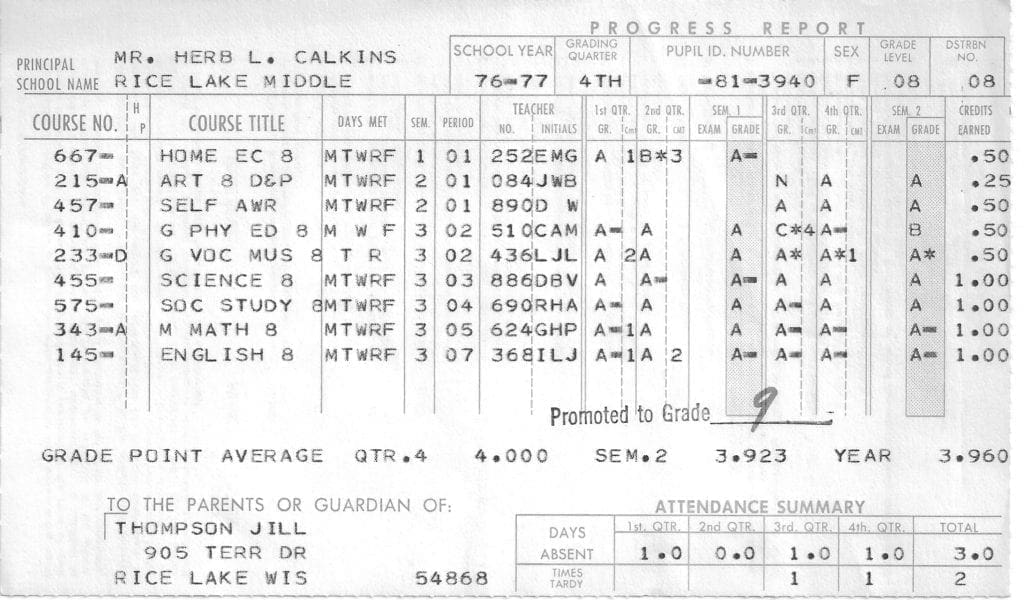

Gradually, more and more A’s began appearing on my report card. When I finished eighth grade, I picked up my report card from the school and skipped all the way home over how many A’s I’d gotten that year. I barely gave it a mention at home though, as it sure was going to feel crummy when no one else cared.

Going into middle school, one of the things I had most been looking forward to—piano lessons—was a total bust by the time it got to me. Pete had worn my parents down with his deep-seated hatred for practicing, and Jeff had polished them off. By the time I was ready to step up to the plate, my folks were done serving.

I ended up taking something like eight years of piano lessons that no one in my house gave a hoot about. Worse, I really only learned to memorize difficult pieces and not to actually sit down and play the piano. The boys also tarnished the playing of an instrument at school, having plowed their way through playing baritone and tuba without much love.

So when in sixth grade I had the chance to pick an instrument for band, I said I wanted to play the drums. My mother wasn’t having it. She had not an ounce of willingness to listen to anyone banging on drums. I blame Pete who, as a child, according to family lore, had one of those Fisher-Price push-along corn poppers whose incessant noise drove my parents nearly nuts. Truthfully, her whole being was stretched almost beyond breaking at that point and the drums might just have pushed my mother over the edge. My second choice was the clarinet, which was similarly nixed. She countered with flute. I said, “I’ll pass.”

Next Chapter

Return to Walker Contents