Musicals were my other first love. Over the course of four years, I was in nine of them. Two were at high school (Annie Get Your Gun and Anything Goes), two at a local theater called the Red Barn (Li’l Abner and Where’s Charley?) where my dad was music director, and five were at the Barron County campus (Bye Bye Birdie, Oklahoma, Brigadoon, Fiddler on the Roof and Hello Dolly!) where my dad was music director for the Summer Music Clinic.

For most of the shows, I was in the chorus, but in Anything Goes I played a wonderful character named Bonnie and had a ball with her song-and-dance numbers. At the music clinic, on my fourth go-round, I asked to be the fiddler, having been passed over for supporting roles in previous years. I then rocketed to the role of Dolly for my final performance.

There was something odd happening behind the scenes when my father was on the casting committee. He informed me once that the others had fought hard to get me into various roles, but he refused. I can’t even guess why he would do that. I’ve never had the best singing voice—decent pitch but not great tone quality—but given all the singing I did growing up, it clearly also wasn’t the worst. My dad later apologized, so let’s move on.

Summer music clinic was a bit of a marvel. Fifty or so high school students from around the state would come for two weeks, bunking in improvised dorms set up in the student center at the campus. On the first Sunday night, there were singing auditions. On Monday morning the cast was posted, with multiple people playing each major part. For example, there were three Dolly’s selected, so while I was honored to be tapped for the final show of a three-night run, I only got to do it one time.

We’d rehearse nonstop that first week, take a breather at an outdoor cookout on Saturday, then do three dress rehearsals on Sunday, Monday and Tuesday evenings in preparation for performances on Wednesday, Thursday and Friday. Then we’d stay up all night and tearfully say goodbye Saturday morning as parents drove off with their bleary-eyed children. It was always really hard when everyone left and went home.

Jeff was introduced to show business early when, one year, they needed someone to play a kid in Annie Get Your Gun and Jeff was called up for the part. Dad, on the phone: “Jeff, jump on your bike and come down to the campus. We have something for you to do.” In the part, he even rode his bike with its leopard-skin banana seat on stage. I was super impressed.

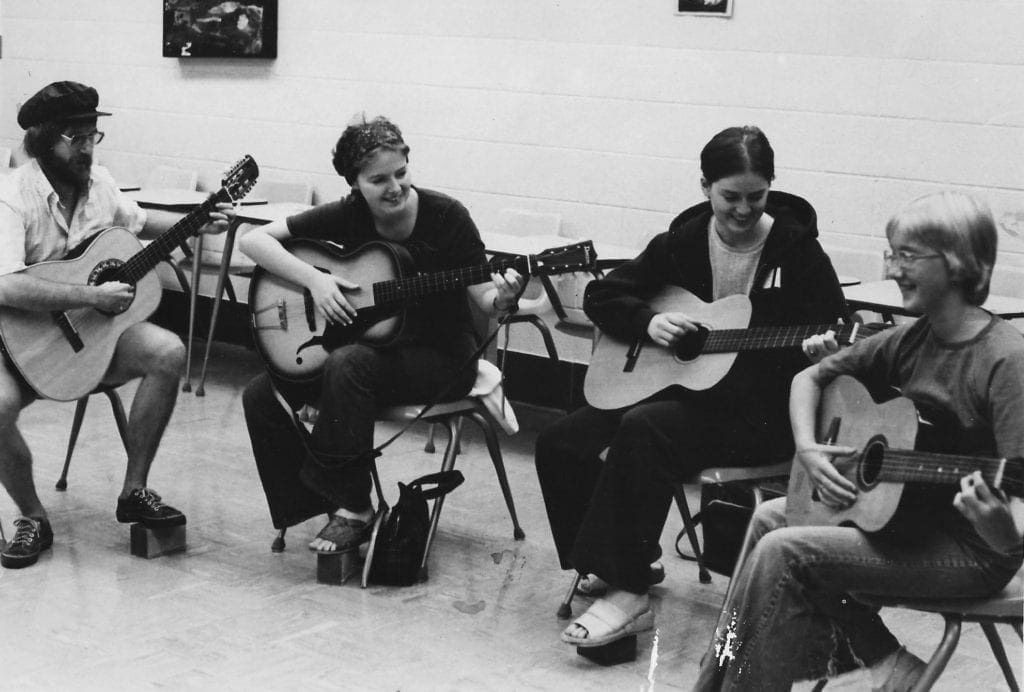

For the next two years, which were the two years leading up to eighth grade, since I wasn’t old enough to qualify for the Summer Music Clinic, I was instead signed up for Guitar Clinic. It was also held at the campus and led by Dad’s colleague and We3 comrade, Don Ruedy, a highly talented musician and artist.

Every day after we finished, I would go sit in the auditorium and watch hours of rehearsal for The Music Man or The Pajama Game. I remember the music for those shows as well as for any of the shows I was actually in.

I also acted in several plays at high school, playing the lead in 1984 and The Butler Did It. A particularly fun show we did was called Brother Goose. In it, I played Eve, described as “an attractive, rather helpless Southern girl” whose boyfriend Wes, “a good-looking boy whose main interest in life is making an impression on girls,” was played by my brother Jeff!

It was at a cast party for a play—really a series of three one-act plays—that I got my first kiss (and hickey!) from a boy named Bill. It was at the cast party for Annie Get Your Gun that I had my first taste of beer. In truth, I’d sipped my dad’s beer before and didn’t like it. But this time I pushed through my aversion and got drunk. Also, another cast member, Mike, had some blackberry brandy and that was delicious. I was an instant fan at the age of 14.

Around the time my father was first getting sober, in the mid-1970s, the idea that alcoholism is a disease was just coming about. This helped a lot with the stigma because in 1975, alcoholism was not a word people were comfortable saying out loud. Recovery was also a fairly new concept. Movie stars weren’t being outed yet for having gone off to treatment for alcoholism.

Around this same time, it was bubbling up that alcoholism might be genetic. I don’t know if I buy into either of these notions. Although, whether it’s nature or nurture, I’ve tried to instill a sense of caution in my own kids, as statistics show there is a higher likelihood for them to wind up in the grips of its insidious tentacles.

In my case, what happened is that I had been raised in a house filled with extreme tension, unpredictable behavior and out-and-out neglect, and all that together left a mark on my soul. I was confused, angry and alternately withdrawn and arrogant. I had no awareness of my feelings, for so much that I felt was unpleasant and therefore pushed down and with any luck, completely numbed.

Alcohol helped with the numbing. At the same time, it allowed me to feel. Sure, what I felt was the feeling of being drunk, but I liked that feeling. It allowed me to relax my uptight inner self of which I had so little understanding. I had no idea who I was and when I was drinking, I didn’t care about that so much.

For the most part, throughout high school I was a normal teenage drinker, sad as it is there’s such a thing as a “normal teenage drinker.” Whereas my brothers were attracted to marijuana, alcohol was my drug of choice. Yes, I smoked pot with them more than once, but it never did much for me. I went to beer parties—sometimes in someone’s house when their parents were gone, or at a gravel pit out in the country—and had a good time. But at home, our household was generally a riot of people yelling, misbehaving and not listening, and no one got away unfazed.

My mother was living her own version of hell during those years. After the divorce, when I went out, I was good enough to wake her to let her know when I was home. Of course there’s no way she didn’t smell alcohol on me, but she didn’t make a big deal of it. By then, I think she was too worn down to care. And I’m grateful for her willingness, whether she intended it as a kindness or not, to let me go my own way.

Later I would tell my own boys when they were in high school, “If you ever get into a situation where you need a ride—like you’re about to get into a car with someone who has been drinking—call me. I promise not to make your situation worse.” I was aware that I had done stupid things along the way, and while we all need to make our own mistakes growing up, someone really could have gotten hurt.

But of course there were limits. In my boxes of memorabilia, I discovered a Proposed Curfew Agreement I had drawn up using our manual typewriter. It seems there was some kind of big misunderstanding following an evening out partying with Janet. This must have occurred while both my parents lived in the house since both of them signed it. Apparently Janet and I had both caught hell—remember, her dad was still a state trooper—and she had come up with a solution for smoothing feathers, which I in turn borrowed. Also, apparently this event predated the typing class I took in high school.

PROPOSED CURFEW FOR JILL

This method of organization has proved to be effective in the household of Janet M.Johnson*,and it is my intention to achieve the same visible results in the Edward G.Thompson household,also. My personal reasons for supporting this proposal are as follows:

#1.I hope this will resolve any possible misunderstandings or questions on behalf of either myself or parents involved .

#2.Considering the amount of time I spend with my good friend,Janet,this proposal may overcome any conflicts in departing time from where we are,especially since when I am expected home,Janet must also receive her transportation at this time!

#3.Last,but not least,this plan is,to the best of my knowledge,the most workable and feasable proposal yet submitted.

The proposed plan is as follows;

School Nights …………………………………………10:30

Weekends …………………………………………….. 12:30

Special Events (Cast Parties,Dances,etc. ).. 1:30

(*Name changed for Janet’s privacy.)

In those days, the drinking age was 18 and drunk driving wasn’t yet a severely punishable offense. I never had a fake ID but I never needed one. I went into bars a few times and didn’t get kicked out, but more often, there were older siblings who provided the libations for the parties. Things did get out of hand a time or two. Like once, while visiting Janet’s sister with Janet and Melinda, I may have over-imbibed on the Kahlua in their cabinet. Janet’s mother threatened to tell my mom if I didn’t tell her. So I told my mom about it. End of story.

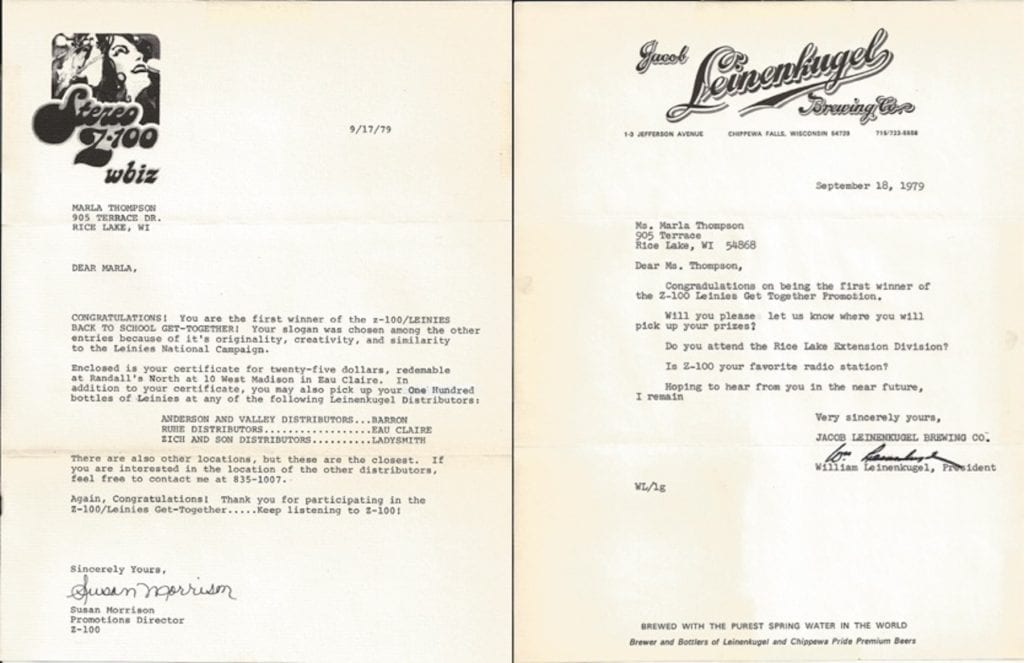

My mom did put her foot down the time I won 100 bottles of Leinenkugel’s beer from a Z-100 radio promotion. At the time, they were running an ad campaign about how to spell L-E-I-N-E-N-K-U-G-E-L-Apostrophe-S. Now owned and broadly marketed by MillerCoors, at the time it was a cheap local favorite—favorite because it was cheap—brewed an hour down the road in Chippewa Falls. We lovingly referred to it as “squaw piss,” thanks to the image of a squaw Indian on the label and the taste.

Here was the jingle I submitted for the Z-100/Leinies Back To School Get-Together contest:

You have to go to school to be able to spell Leinenkugel’s.

And you have to be able to spell Leinenkugel’s to be cool.

So go to school and get cool!

For many years, there had always been a case of Leinenkugel’s longnecks in our cupboard. But now my parents were divorced and my dad was out of the house. Oh, and I wasn’t yet 18, so I had used my mother’s name for the contest. My mother seldom drank, but it’s hard to take a pass on something that’s free. In the end, Jeff may have ended up with 100 bottles of beer on his wall.

So while one might think that if you grow up drenched in the unpleasant atmosphere of alcoholism, you would run far and fast in the other direction. But it often doesn’t work that way. Alcohol is a readily available, socially acceptable drug that does the trick: It’s a depressant and it shuts down unhappy feelings. But it’s a one-trick pony, so it eventually shuts off happy feelings as well. Then it blindly goes on creating more and more unhappiness it must then work to try to overcome. This is a vicious circle that never ends well.

Alcohol is one option, but people can and do find any variety of other addictions. All are intended to fill the gaping hole in a person’s soul but only perpetuate the life-denying tragedy of numbness. When forced to give up one’s first choice, there are plenty of other options to chose from: food, exercise, shopping, gambling, sex and playing video games, to name a few.

Sometimes opportunity is a key culprit in launching a person’s spiral into addiction. Case in point, when the Native American Indians started putting up gambling casinos in the area, people suddenly began losing their farms, left and right. Since my childhood, Gamblers Anonymous meetings have sprouted up throughout the region. The little town of Turtle Lake, barely a crossroads in my youth, now sports a multitude of hotels and restaurants, along with fresh busloads of people arriving daily from the Cities—which is how locals refer to Minneapolis and St. Paul, an hour and a half away—to visit the St Croix Casino.

[Addendum of Sorts, from my mom about “…I won 100 bottles of Leinenkugel’s beer…”: Jill really held ownership to this beer even though she had submitted the jingle in my name. She wanted to share it with her friends at our house. They were all under age to be drinking and I said, “No!” She was furious with me. I don’t know who ended up with the beer. Within a short time it was gone. I didn’t ask any questions.]

Next Chapter

Return to Walker Contents