The gig at Sawyer lasted a few years, but work for me was slow there too. A lot of the people were terrific but I found it hard to fit in. These were ad agency types and I had a degree in chemistry. I was a bit of a square peg in a round hole. More aptly, I sometimes felt like a turd in a punch bowl. Some of the immature graphic artists made working there unpleasant—I found dead palmetto bugs in my desk drawer one day—and management turned a blind eye because, “Oh, you know those creative types…”

The agency was looking to make a name for itself as a creative powerhouse, but it can sometimes be difficult to push the envelope with staid customers in the b-to-b space. One solution is to do pro bono work where the client may offer a bit more leeway. As a result, Sawyer worked hard to become the agency of record for The Atlanta Project, an initiative headed by Jimmy Carter.

The mission of the Atlanta Project was to reach out to individuals in underprivileged communities and help them get established in a job. The goal was to create a positive ripple effect. My claim to fame is helping conceive their tagline: The Atlanta Project Works, One Life at a Time. So, for example, the poster we created read: One on One, Heart to Heart, Hand in Hand, The Atlanta Project Works, One Life at a Time.

I also worked on creating radio spots and TV ads. While driving a woman home to South Atlanta after a commercial shoot, I told her that I could also drive her to an upcoming event where she might even have an opportunity to meet President Carter. “That’s Ok,” she said. “We see him all the time. I’ve met him before.” Jimmy Carter is a man of remarkable character who has worked tirelessly for decades on behalf of those in need.

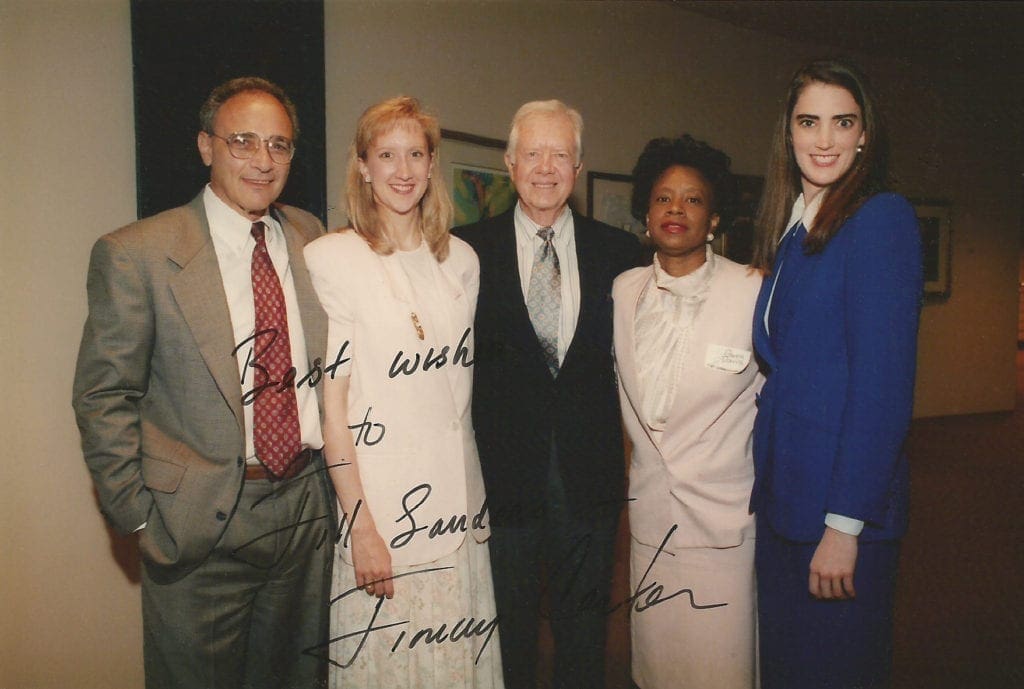

Our agency had two opportunities to meet with Jimmy Carter, first presenting our ideas and then showing him the finished work. On both occasions I was able to have my picture taken with him; the second time, he said, “It’s nice to see you again.” That man is a class act and with that comment, he made my year.

There were about 50 people at Sawyer Riley Compton, which was owned by three men—Mr. Sawyer, Mr. Riley and Mr. Compton, obviously—who hailed from a rural part of the state. On the upside, they worked hard to create and maintain a family atmosphere. If someone left, they gave them a piece of pottery as a remembrance. When I resigned, I carried with me the thirtieth clay pot I’d seen walk out the door. Turnover was an issue.

I went back to working for a boutique (aka, teeny-tiny) ad agency—my, how far I had fallen from my early days working for Fortune 500 companies—called Donino & Partners. They had a big telecom company, MCI, as a client, and then lost them the week I started. First I mastered the video game Tetris, then I finished cross-stitching the Christmas stocking I was making for Charlie.

I’d already made two for Rick and myself, but the pattern for Charlie’s was significantly larger and harder. Years later, I would struggle to finish Jackson’s before he was old enough to say, “Hey, where’s my stocking?” I joked that was the limiting factor on how many kids I could have: I didn’t have it in me to make another stocking.

Actually, there was another reason I couldn’t have any more children: the birthday parties. When the boys were at Apostles Daycare, the rule was that if any parents threw a birthday party for their child, they could invite other kids from the class as long as they invited the whole class. We got invited to a lot of birthday parties.

In truth, that was our social life. It was a great way to get to know other parents who of course always also stayed for the entire party. We also gave a lot of parties. And we exhausted all the options: Chuck E Cheese’s, Chattahoochee Nature Center, gymnastics, bowling, you name it.

Among my favorites were the parties we hosted in our own camper. Rick and I had bought a popup camper from my brother Jeff when the boys were very young—Jeff’s family was upgrading—and set it up in the driveway. There was even a stream for the kids to play in. We’d hung a piñata from the overhang above the garage and the boys had a big time swinging at that, followed by a sleep-over in the camper.

You have to watch out for those swinging bats though. Charlie was at a party at a batting cage one year with his baseball team of 10-year-olds, when he accidentally stepped into the path of a swinging wiffle ball bat. It was fortunate that the father of one of the kids on the team was a plastic surgeon because Charlie’s nose needed mending. They had to wait three days for the swelling to go down before doing the surgery, and in that time, the team had a game. Dr. Yellin said, “Might as well let him play if he wants. What’s the worst that can happen? He already has a broken nose.” He played.

Next Chapter

Return to Walker Contents