In 2005, I woke one morning, a dream full of bright lights still filling my vision and a message saying I would be “moving onto something new and exciting” echoing in my ears. A short while later when they announced a new position at work for a training manager, I knew that would be me. I say “I knew” as though I actually knew. I did, in fact, have a “knowing,” but I also had all the normal jitters that accompany applying for a new position.

A handful of people interviewed for the job, all women with children who thought it looked like an interesting position that wouldn’t require much travel. On that last front, they were wrong. As I finished my chat with the head of HR, which is who the position would report to, he said, “There’s one question that everyone else has asked that you haven’t.”

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Salary and grade level for the position,” he responded. “They want to know if this is a lateral move, a promotion, or what.”

As for me, I didn’t really care. I wanted out of the marketing manager spot where I felt overlooked and seriously underappreciated. The head of HR assured me it would be a step ahead. Imagine his surprise when he actually bothered to look at the facts of the situation and saw that this was a lateral move for me, at best. He squeaked out a thousand-dollar salary increase to give me, mostly to save face.

This scenario offers some insight into how transparency worked at Solvay, which was the name of the Belgian-based company that had acquired us a few years earlier. In short, there was little. It explained a lot when I learned that the internal motto of the company used to be: “Well hidden is well protected.”

In the end, I got the job as the training manager, or as I thought of it, I left the company and went to HR.Toward the end of the year, I found myself booking an around-the-world airline ticket that would have me presenting a new training program to employees, not just in the US, but also in China, Japan and Europe. I would end my loop in Italy, sharing what we had developed with managers at a sister-division on Thanksgiving Day. Happy Holidays!

During my stint in HR, I was given access to the usual drives that people in HR had access to. This is interesting, I think I’m looking at the salaries for all our employees.(Trust me, it’s not as fun to know as you might think.) Also, in my capacity as the new training manager, I was invited to sit in on the succession planning meeting, in an effort to identify what kind of training might be needed, and where. Except for the slot of marketing communications manager, my name did not appear. ‘This,’ I thought, ‘is why I’m now in HR.’

A big part of my work in this lifetime has been to become comfortable with being a woman. All my life, ever since it was “the boys and Jill,” I’ve struggled with that part of me. Eventually, I figured out that that’s not a part of me, it’s all of me. That’s who and what I am, a woman, and this is not an inherent flaw. But to my way of seeing things, unconsciously, if I had just been born a boy, I would have fit right in with the pack. So this is what I had recreated in my work life. From the perspective of the Pathwork teachings, this is what I had surfaced so I could see it, work with it, and thereby heal it—in me.

Please note, whenever we take this approach of claiming self-responsibility for our inner work, this doesn’t let the other off the hook. We’re all in this soup together and there are always plenty of fingers to point, but blame gets us nowhere. What we need to do is find the grain of truth about our own faults, which become exposed through our difficult encounters.

The wrongdoings of others are never the cause of our problems. We are. They are just what bring our own distortions to the surface. Once we heal them at their root, where they live in us, we can go back to the source of our friction and attempt to find common ground. Before that, we’re too emotionally charged and likely to make matters worse.

So here I was, a competent woman working in a male-dominated company, and I was overlooked. To be clear, it’s not that the place didn’t have a number of talented women, some at reasonably high levels. None, of course, over the 15 years I worked there, were at the highest levels, save for an HR manager. I thought of this as the Sperm-and-Egg Effect: One got through, quick, close the gate!

By now, I was deep into my Pathwork studies and had also uncovered an inner split in my psyche. Part of me wanted desperately to be seen, and part of me feared being seen. Sifting through my childhood, it’s not hard to see how this had surfaced in this lifetime. Briefly, when I wasn’t seen by my father, it was painful. And yet, when I was seen by my mother, that managed to hurt too.

I was valued more for my contribution to housework than for who I was. My goal, when I was in the basement, was to sneak up the stairs, through the laundry room, and into my bedroom, before my mother spotted me and put me to work. As a result, I had developed something I later thought of as my own personal cloaking device. It was the ability to show up in a group of people and hide in plain sight. And now we’re starting to see how I contributed to the creation of my own reality.

So here it was, in living color, the pain of not being seen at work, which was also coupled with the pain of how it felt when I was seen. For example, one year as marketing manager, after spending all my time managing conflicts surrounding some colleagues in Asia, I was dinged in my review for the fact that there was so much conflict. Are you serious?

Don’t get me wrong, these were really smart people. It was a crowd of engineers and PhD chemists all of whom had likely graduated at the top of their class. But soft skills were another matter. As the training manager, I brought in outside help in this area. And by and large, it was a kind culture; people didn’t yell at each other. And work-life balance was generally respected. When we were in the recession in 2009, our leadership came up with a clever way to make up for the company’s financial shortfall: During the last four months of the year, everyone had to take a week of unpaid vacation. ‘Excellent’, I thought. ‘I’m coming up a little short on vacation days this year.’

Regardless of what it said on the succession planning chart, when the global marcom manager role opened up, they went first to Marla, the woman who had initially hired me after interviewing just one candidate. She said, “The person who knows the most about marketing communications in this company is Jill. Ask her.” And that’s how I came back into marcom, one of my great loves in life.

For the next several years, our global team of roughly eight to ten people would climb a mountain and create marketing communications that were far-reaching and well-crafted. Through a quarterly presentation to the business’s highest-level managers, I earned the respect of at least one person, the head of R&D. George would go on to become the president of our division and an ally for my efforts.

George replaced Roger who went to Thailand to lead our activities in Asia. As he was leaving, Roger needed to sell his convertible BMW and give away his cat. Roger had survived the flight from Europe with the cat when he’d moved back to the US, but didn’t think they could do that long flight to Thailand together.

By then, I missed my cat Blue who had apparently met his demise in the woods surrounding my house. (And this is why some people are opposed to cats going outside. Point taken.) Roger tried to make it a package deal—Take the cat for $30,000 and I’ll throw in a car!—but after all was said and done, the car went to my colleague Shari, and I got a cat worth $30,000. You can find a picture of Henry—formerly Samson, he too apparently grew into his name—the other best cat in the world, on the cover of this book. (Note, Henry loved the screened-in porch I added to my house and I didn’t let him roam any farther.)

George stepped into the role as president just as the company was approaching time for the triennial global sales meeting for close to 300 people. And he nominated me to be the one to manage it. The sheer number of moving parts involved in orchestrating such an event is staggering, but our global marcom team pinned the tail on that donkey. So much so that three years later, we were asked to do it again. Both times, it involved months of putting my life on hold to be able to manage the bandwidth of energy required to execute an event of that magnitude.

One of the challenges I’ve mentioned with this company was their reluctance to take action with an underperforming employee, and I had one of those. His primary fault was that he continually withheld so much information from me, I couldn’t see his mistakes until it was too late to correct them. And he made some doozies. Worse, he wouldn’t change his ways.

Realizing by then how truly useless our HR was, I knew I was on my own. I was involved in a mentoring program that gave me access to a bright, dynamic female executive from another company to help me work through problems. I vented about this one with flames shooting out my ears. She suggested I might consider something that had been a common practice in her company in the past. They called it “pass the trash.”

Here’s how it worked in my situation. I saw that this employee would be travelling with someone further up the chain of command, from our corporate offices in Houston. And I knew there was another communications group in that location. I called this high-level person, an attorney, and said I just wanted him to know that this particular employee might be looking for another job—which was true, and it was so unfortunate he hadn’t yet gotten one—so better not to share too much sensitive information about a delicate topic our company was currently handling. The rest was easy, as shortly thereafter an offer had been made to promote my little darling to go work for corporate communications. My work was done.

Around the time of the second global meeting in 2011, our company had been restructured and our division merged with that sister company in Italy. That’s when the wheels started falling off for me. I’ve long likened marketing communications—which consists of websites, literature, trade shows, and the like—to handwriting: People either have good handwriting or they don’t, and seldom does that change over time. In the case of marcom, people either get it or they don’t, and those who don’t get it seldom convert into those who do. George got it, but he had gone back to leading R&D. Whoever was devising the org chart for the new business, didn’t get it.

For the previous five or so years, everything my group did was in support of global markets. Unlike inexpensive plastics that are made in large volumes for low prices and shipped regionally, our materials were made in relatively low volumes and shipped to customers all around the world, in all variety of markets. While some markets were more regionally focused than others, most had activity in multiple global regions.

In the new organization, however, they divvied up our marcom activity so that the former marcom manager in Europe, with whom I worked very well, was to handle activity in Europe, I was to manage activity in the US, which in most cases was not our strongest market, and for Asia, our largest growing region, an administrative assistant without a college degree was put in charge. She and I also worked well together, but this way of working made no sense.

Further, as people left our department, they were not allowed to be backfilled. Over the course of a few short years, the department I had built had been dissolved. After I left marcom and went back into sales, the two people who remained moved out of our specialized marcom area—I’d converted the old library into a vibrant hive of oversized cubicles and workspaces—and back into regular offices. As Kimberly, one of my spiritual teachers, would have said, “And something returned to nothing.”

As a marketing manager, every projection of future sales I ever saw or created myself was a proverbial hockey stick: unending growth projections leading to blue skies ahead. That’s the world we live in, where every quarterly stockholder report demands an end-over-end uptick, everything always on the rise. Trouble is, that’s not reality.

Creation happens in circles, with every ending creating an opportunity for a new beginning. To measure endings as a failure then is to miss the cyclical nature of life. Further, while in the greater reality good can endure forever, here on this dualistic plane we also have distortions and negativity—the downside of life—and that’s what eventually grinds us to a halt. This creates a turning point, a chance to make another choice, making any crisis a beautiful problem potentially leading us to a better solution.

I moved on early in 2012 when an opportunity as a sales development manager in the healthcare market opened up. Actually, I had told the head of sales and marketing in 2011 that I just couldn’t do this anymore. He said, “Do one more global meeting, then we’ll talk.” Then he said, “All I’ve got to offer you is a job in sales.”

Driving home on Friday evening with this offer fresh in hand, I was pissed. Going into sales was like going back to square one! I’d started out in sales and had come a good long ways since then. The next morning, getting ready to attend an all-day swim meet for Jackson, I had an idea: ‘How about I try this on for size, just for today. If, at the end of the day, I still hate the idea, I can pass.’

The healthcare team was small but strong, and the applications were very interesting. Plus, it had been awhile since I’d traveled much in the US, so that sounded like a nice change of pace. And given my attitude toward the company, I didn’t hate the idea of working from home. Once I got over my pride, I couldn’t talk myself back into staying where I was.

But beyond all that, Jackson had been in kindergarten when Rick and I divorced, upsetting his little apple cart, no matter how much I wished it could have been otherwise. I wanted to take this job as a way to maintain stability until he graduated from high school. Every day, for two years, I made peace with my decision.

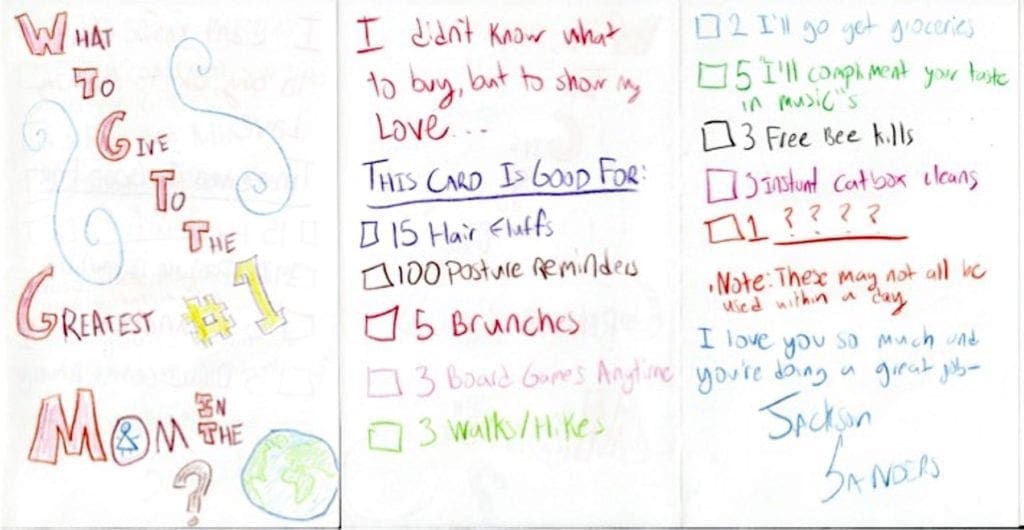

Handmade Birthday Card, from Jackson Sanders, circa 2012 (~age 17)

Cover: What To Give To The Greatest #1 Mom in the World?

Inside: I didn’t know what to buy, but to show my love…

This Card Is Good For

☐ 15 Hair Fluffs

☐ 100 Positive Reminders

☐ 5 Brunches

☐ 3 Board Games Anytime

☐ 3 Walks/Hikes

☐ 2 I’ll go Get Groceries

☐ 5 I’ll Compliment your Taste in Music

☐ 3 Free Bee Kills

☐ 3 Instant Cat Box cleans

☐ 1 ??????

Note: These may not all be used within a day

I love you so much and you’re doing a great job—

Jackson Sanders

On Easter of 2013, midway through my final two-year push at Solvay, I found myself walking in circles in my kitchen riding the edge of how much pain I could tolerate. A top left molar was intermittently barking like a mad hyena when it wasn’t being quiet as a lamb. Oddly, I was glad to at least know the source of my discomfort, as a few weeks prior, I had feared the worst.

I had been sitting in my office chair when I’d reached behind my right ear and found a lump. What on earth? I showed it to Pete and he agreed it was strange. I gave it a week to go away, then I went to see a doctor. She sent me on for a chest x-ray on a Friday afternoon, which led to having a CT scan scheduled for Monday. They wanted to investigate a “possible mass in the left hilar region of my lung.” Or maybe it was a shadow. Hard to tell.

There were two points to consider. First, if the mass diagnosis was correct, I was a dead man walking. For to have it so far away from the lump, on the opposite side of my body, meant curtains. At least that’s what Google was telling me. Second, Jackson was heading to Europe on Monday morning with his French class, and I didn’t want to say anything that might spoil his trip. But I was scared.

I only told Pete about what was going on, since he already knew about the lump and I needed someone to help me carry this. Recollections about the family blood disease started filling my head. I felt badly for the CT scan technician, because I cried through most of the procedure. I couldn’t help it.

In the end, my lungs were clear. Which left me with the mystery of the lump. I went for a healing session with Kimberly who, with my permission, shared the situation with her husband, an acupuncturist and like Kimberly, a Barbara Brennan healer. She called me later: “Warren suggests checking your teeth.”

My dentist got me in right away for a panoramic dental x-ray, but it turned up nothing. Then that weekend, the shooting pains started up. The morning after Easter, Dr. Gilbert immediately referred me to an excellent oral surgeon. When I arrived for my appointment, the lambs were all in their stable. When asked to point to the pain-face that best represented me the day before, I went with nine out of ten. One more click on the dial and I’d have needed some morphine.

The doctor pulled the offending tooth, which he later confirmed had cracked roots, and sent me home with pain meds. Here’s where I made a strategic mistake. Not wanting to wake in the middle of the night with pain like I’d had on Easter, I decided to take the hydrocodone before heading to bed. Jackson was at his dad’s, so I was by myself.

In the middle of the night, I woke up and felt absolutely awful. I was nauseous and delirious, and thought I needed to get some food in my stomach. I made it to the kitchen, got out some pudding, and that’s about as far as I went. Passing out and sick in the middle of my kitchen floor at 2am, I called Peter to come help me.

But after I came to, I couldn’t stop throwing up. So Pete got on the phone with my doctor and got me a prescription for anti-nausea medicine, which he then went and picked up for me. My brother had my back.

After the storm died down, the lump went away. Its location never made any sense, positioned on the other side of my head from the broken tooth. A few years later, I was living in DC when I went for a normal dental check-up. All seemed fine with my tooth implant, but I had some concerns about receding gums.

A week later, visiting a periodontist in Dupont Circle for an evaluation, he noticed some drainage happening near the implant. Further investigation showed I had a serious abscess on the back molar next door, which my dentist—using her film-era x-ray equipment—had missed. Roll forward one more root canal and I was good as new again. On my next visit to that dentist, I saw she had upgraded to digital x-rays and I felt the solution was well in hand. And I was grateful to feel the universe had my back.

[Addendum of Sorts, from my mom about “Recollections about the family blood disease started filling my head.”: Please put that concern to rest. There is no way you have the disease, referred to as HHT by the medical community, or could pass on the disease to your descendants. It is one bad gene and if l don’t have it, you can’t have it or pass it on. I feel so blessed to have been ‘passed over’. So many in the family suffer with it. I thank God that I don’t have it, and I’m especially thankful that I couldn’t pass it on to you or your brothers.]

Next Chapter

Return to Walker Contents