The old house we lived in was, I’ve been told, quite a dump when my parents bought it for the grand sum of $6500. (My mother cried—and they were not tears of joy—the first time my dad showed it to her.) I don’t think it’s a matter of comparing that sum to today’s dollars. No, it’s a reflection of how much work the place needed. But of course, I didn’t know any of that when I was a kid, and my parents had made good headway by the time my memories kick in.

I had my own bedroom at the top of the stairs decorated with a few of those Big Eyes pictures they’ve made a movie about. Between my bedroom and my parent’s bedroom was a laundry chute for chucking dirty clothes down into the basement. Since it had access from both rooms, it created a fun obstacle course for my brothers and me to scoot across, going from one room to the other and thankfully never falling to the concrete floor far below.

As an adult, I have learned that the reason I was so often huddled next to the heat register behind the chair in the living room is that the house didn’t actually have any heat ducts upstairs. While I make no claim to have walked five miles to school in the snow, uphill both ways, I did survive childhood wearing homemade mittens and with no heat in my bedroom. Forced to relive it, I would ask to at least be able to take my North Face gear with me.

We had a claw foot bathtub in the upstairs bathroom, long before they turned into a treasured throwback, and using a reel-to-reel tape deck set up in my brother’s bedroom, my dad would record a radio program that aired weekly. I was desperately curious about what he was doing, but of course if he put the microphone to my mouth and let me speak, I became shy and sounded like an addled idiot. Self-confidence was not my strong suit growing up.

I learned about the birds and the bees from a record that was played for my brother Pete on the enormous console that housed the turntable and radio. Also, my mother gave piano lessons on the upright piano in the dining room. My breastfeeding stopped at 10 months, mostly because I was ready to be weaned, but also partly because my cries for food interfered with the piano lessons. My mother had been the church organist in Barron and, after moving to Rice Lake, she began playing the pipe organ at the Lutheran church. Sixty-some years later, she continues as church organist to this day.

Kindergarten, in the 1960s, was a half-day affair, which was a hassle for a family with two working parents. (When my own kids went off to kindergarten, I was grateful it went the whole day.) A plan was devised for me to spend the other half of the day at my friend Jill’s house. I’m not sure daycares even existed back then.

Jill’s mother was kind to me but she was strict. I remember standing in the hallway as Jill got her mouth washed out with soap for talking back. This form of punishment has since been called out by parenting experts as being cruel, even child abuse, and not discipline. Back then though, it’s what was done.

As life unfolded, I lost contact with Jill, but from time to time would get an update that she was struggling with anorexia. Years later, in 2008, while at a poetry retreat, I would write this poem about her:

Rough

When I was five,

I spent mornings with my friend.

Kindergarten was in the afternoon.

My friend’s name was Jill,

Just like mine.

Her hair was brown and mine was blonde.

A man at a store nicknamed us

Chocolate and vanilla. It stuck

Like the top of a cone dumped on a hot sidewalk.

I remember playing together in her basement.

She got a rock tumbler for Christmas

That turned rough, ugly agates into gems.

I was amazed.

In high school, my Dad said he had seen Jill.

Blonde now and

Skinny as a rail.

Later the update through my mother was:

Her mom didn’t know if she’d see 30,

Anorexic fifteen years by then.

Looking back, I recall other things,

Like her mom washing her mouth out with soap

For talking back.

We were five.

I wonder if it’s possible to ruin a

Perfectly good rock

By tumbling it.

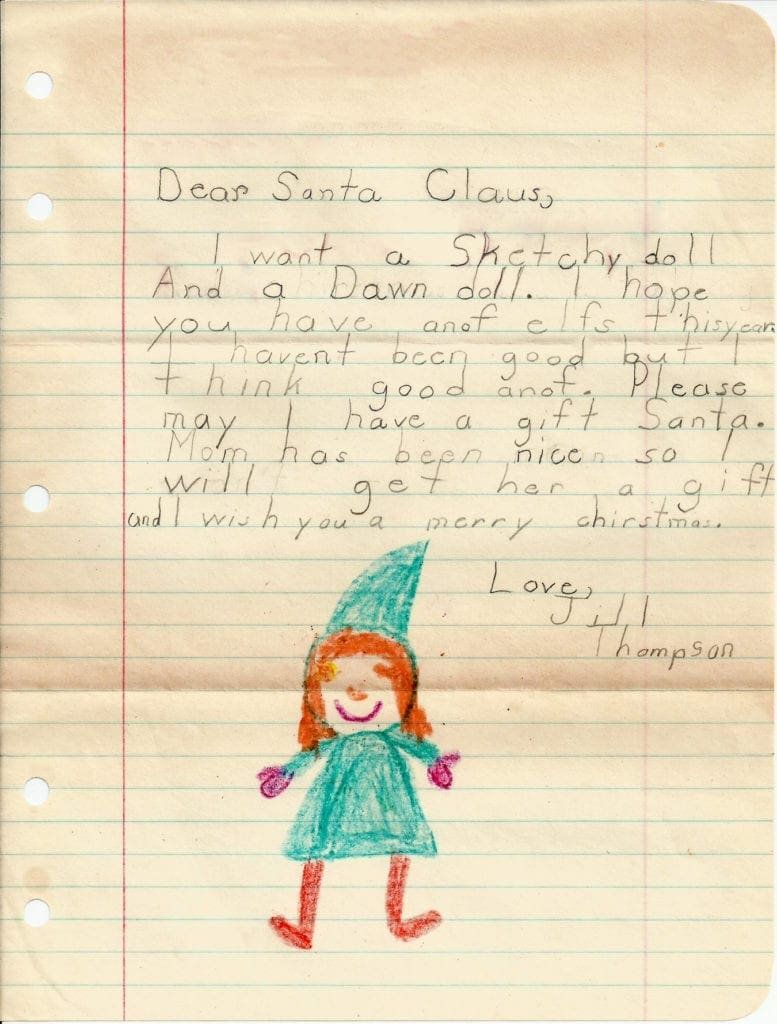

When I was eight, my mother was cleaning out the upstairs closet—probably while we were packing to move—when my brothers decided it was time for me to know the truth. Up until then, someone had been playing the part of Santa Claus every year, dressing up in a Santa suit and ho-ho-ho-ing in a booming bass voice as he sat us each on his knee and asked us what we wanted for Christmas. Who knows what I said—chances are I froze like a reindeer in headlights—but I do remember being able to see up underneath the fake beard. I was neither surprised nor disappointed, but just aware there was a man underneath that costume.

Most years, as Santa left out the back door of Grandma’s house, or wherever we were, the kids were herded to the front window where we would be forced to look in the sky for his departing sleigh. The grown-ups wouldn’t let up until we relented and said we saw it and heard the sleigh bells. I always found this highly annoying. I’m not sure if I was more disturbed that I couldn’t see and hear what they did, or that they made me admit I saw and heard something I didn’t.

So as the closet was emptied of its contents, my brothers took it upon themselves to show me the box containing the Santa costume. I was floored. Dumbfounded, in fact. Sure, I knew there was a person under that suit, but I had no idea it was my own dad!

I don’t actually recall the year my dad made an extra-Herculean effort to keep my brothers’ imaginations alive, but it’s a story worth telling, even if from hearsay. To show that the sleigh and reindeer did indeed fly off into the air from our backyard, he strapped two-by-fours, on edge, to the bottom of his feet. Then walking our dog Pepper between his legs, he shuffled his way through the snow from our house to the back end of the garage. When he got to the corner of the garage, he picked up the dog and jumped sideways to land behind the garage. (Later in life I learned that most people just put a half-eaten cookie or carrot by the fireplace on Christmas Eve and call it a night. Pikers.)

Parked on the other side of the garage was our camper, an egg-shaped thing painted half-green and half-white. We often camped not far up the road at Sleepy Hollow campground, which was nestled next to a charming little stream. At some point, my brother Jeff, a talented artist and craftsman, made a miniature camper for my Barbie out of a shoebox. The lid, on which he had drawn a window and a door, came off from the side, revealing a little table and bed inside. Even then, I could see how clever and creative it was.

I actually had two Barbies to play with. One Barbie was the real deal, with blonde hair and the obligatory teeny, tiny waist. The other was what I called, at the time, a “mulatto”: A biracial doll of black and white descent. Her skin was a light tawny brown, her eyeshadow a lovely blue—á la Lieutenant Uhura on Star Trek—and her hair a helmet of tight black curls. One of her boobs was forever dented from when one of my brothers smacked her against a table. I have no idea where she came from.

The real Barbie suffered a permanent injury when, after moving to Rice Lake, I took my dolls to my friend Julie’s house to play. Julie had a fabulous set of Barbie doll-sized horses (I was really too old for dolls by then, but I seriously liked those horses), and when I attempted to sit my Barbie on top of one of them, her hip joint snapped. She was never the same after that.

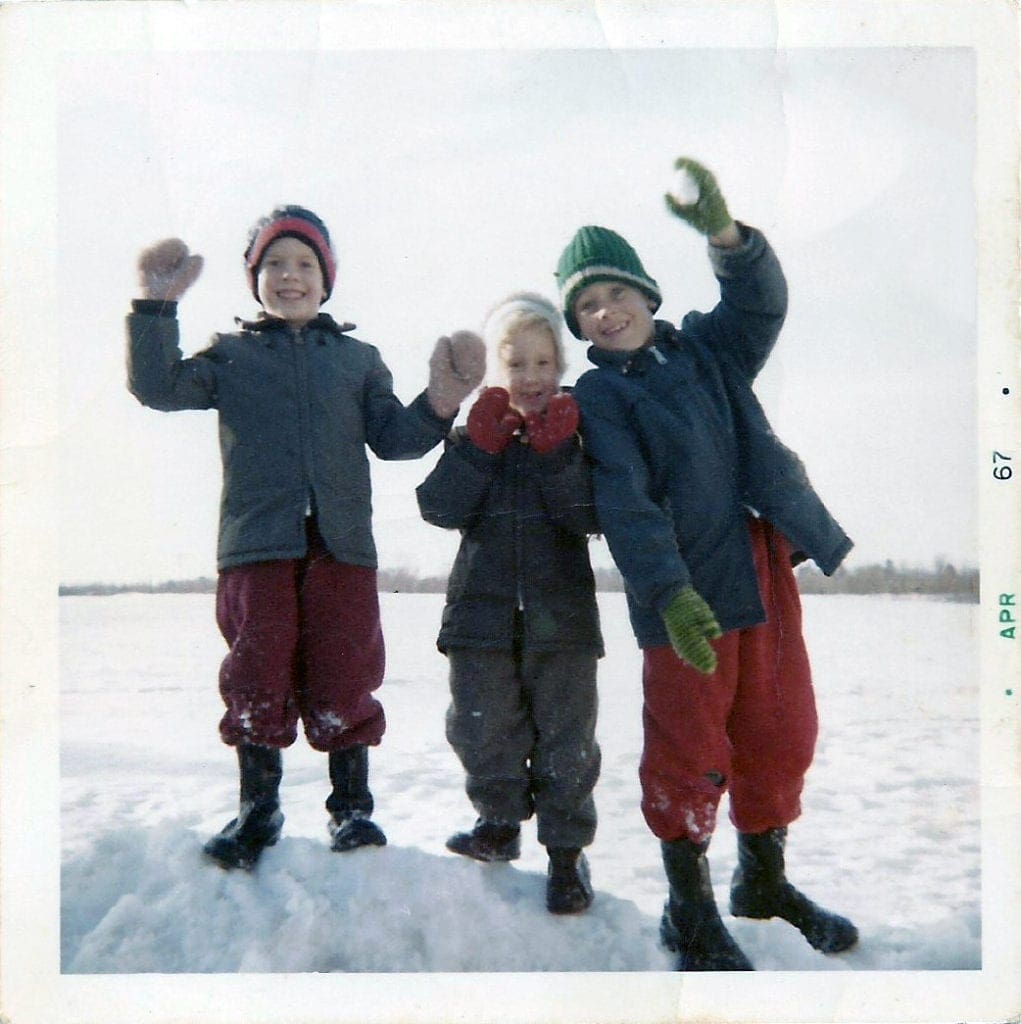

We swam when we went camping, but I don’t actually remember learning to swim. With no other children living near us in Barron, from an early age I just tagged along with my brothers and did what they did. In many ways, this gave me a leg up on life. My mother never did learn to swim and it’s a gap that seems to have haunted her entire life.

As a result, she expressed a lot of angst about our safety when swimming—although it was a widely accepted truth back then that you must wait one hour after eating to go swimming, else you’d get a leg cramp, sink like a rock, and drown—probably projecting her own fears onto us. But she couldn’t have done a thing to save us if she had wanted to.

I do remember being signed up for swimming lessons at the Barron swimming area, which was located along a stretch of the Yellow River not far from downtown. I didn’t understand why everyone else in my class was acting afraid of the water since by then I had been swimming in even the deepest of the three swimming sections. Exasperated, the teacher tried to get us all to at least blow bubbles in the water. Well, no way I was doing that. ‘That’s stupid! I’m already jumping off the high dive,’ I thought.

Swimming lessons, then, were a bust. Which isn’t to say I was a very good swimmer. My own kids would later grow up swimming in pools, learning the proper form for breaststroke, backstroke, butterfly and freestyle, but I only knew how to get myself out to an inner tube in the middle of a lake. So I can do sidestroke, which isn’t really a thing, and an overhand crawl in which you keep your head above water so you can see where you’re going. As I was told, when you’re a lifeguard in a lake, you need to keep your eye on the prize; you can’t be putting your face underwater while you swim.

My birthday falls at the end of May, so sometimes I would take a small group of friends to the cabin over Memorial Day weekend to celebrate it. (This was dicey, bringing friends to the cabin, not knowing what my dad’s condition would be.) It was always a badge of courage to go for a swim on my birthday weekend, considering that typically the ice had only melted off the lake a few weeks earlier. It basically felt like swimming in a giant tub of ice water.

[Addendum of Sorts, from my mom about “…the house didn’t actually have any heat ducts upstairs.”: That was true, but there were ceiling registers that allowed heat to travel upward to the bedrooms upstairs, albeit not enough to get overly warm up there. This was quite common in those older houses.]

Next Chapter

Return to Walker Contents