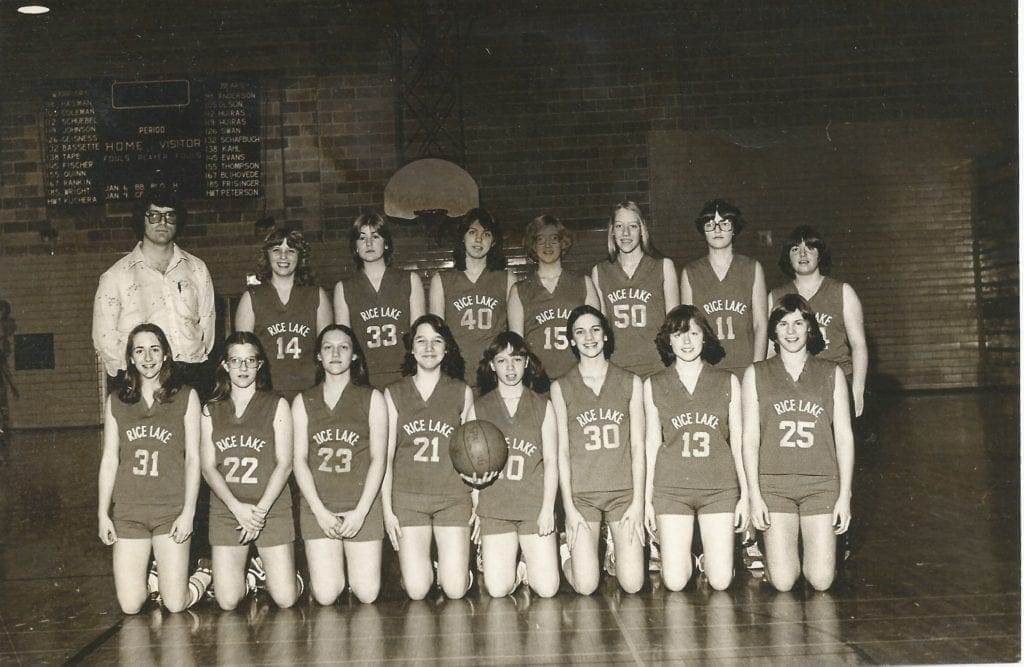

Heading into my freshman year of high school, I once again didn’t make the cut at cheerleading tryouts. So instead I went out for the basketball team. According to the coach, I had a fairly high vertical jump, but beyond that, I was awful at the sport. I’m not sure we won a single game—although our team actually had some genuinely good players—and I nearly scored a basket for the other team. We were playing Cumberland and my cousin Trudy was on that other team. So embarrassing.

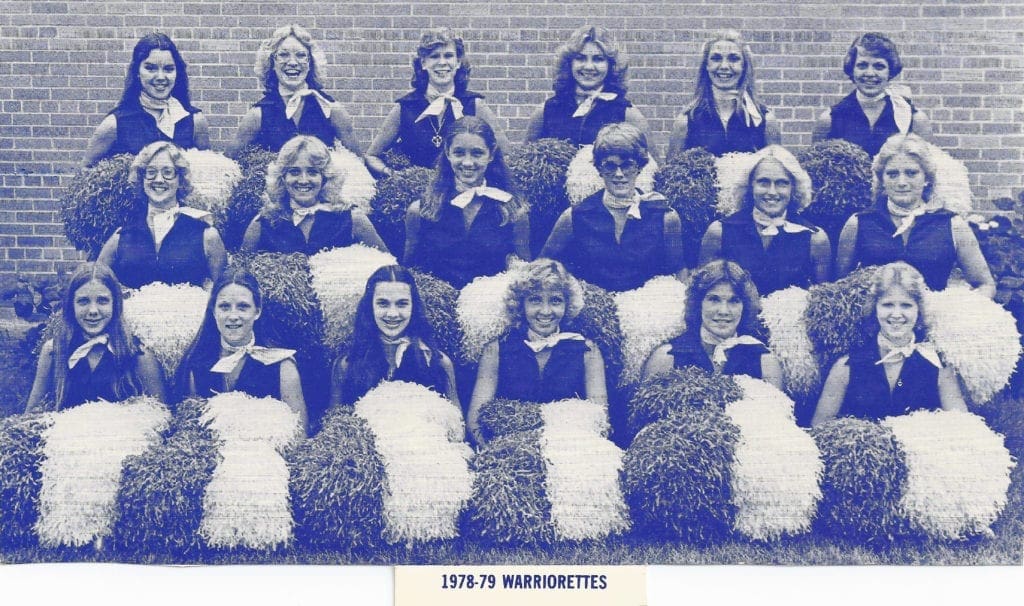

Then in the spring, I tried out for the pom-pom squad, a dancing group of 18 girls called the Warriorettes, and was lucky enough to land one of three open spots; Laurie and Julie snagged the other two. Melinda would make the squad the next year.

Being a pom-pom girl was one of my first loves. For the next five years, it would occupy hours of my time and fulfill me very deeply. I loved marching onto the field and in parades with the band, stepping to the cadence of drums; I loved creating challenging routines and nailing them with precision; I loved walking off after the performance to the wild cheers of the crowd.

Let’s be clear, we were not the cheerleaders on the sideline during the games. We were the ones in front of the band at halftime, shaking our pom-poms and killing it with our kick-line, performing a different routine to different music every game. During basketball, we did complicated routines to popular songs that blared over the low-fidelity speakers. Once, the gymnasium speakers cut out completely halfway through our performance, apparently having tripped a circuit. Awkward! We worked our buns off and we were good.

My junior year, during basketball season, some college pom-pom girls from UW-Stout (or possibly LaCrosse) came and taught us an exceptionally fun but tricky routine to Charlie Daniels Band’s The South’s Gonna Do it Again. After they left, I was the only one of us who remembered all the moves, so I turned around and re-taught it to the squad. We were a bunch of white girls in Northern Wisconsin wearing bandanas around our necks and white gloves with fringe sewed along the edge, which we waved around like pistols during the performance. I doubt any of us knew what that song was about. I know I didn’t

Other standout performances included wearing gym suits, sunglasses and whacky hair to do a punk routine to Devo’s Whip It (something we’d lifted by watching another high school at a pom-pom competition), and wearing colorful satin bibs and hats for our annual jazz routine.

After-school practice space was always tight at the school, so we used the theater lobby my first year and the cafeteria the other two, pulling up tables and pushing them aside to make room. But we still couldn’t get the whole height-line—we each had our position in the line, tallest to shortest, with the tallest girls in the center—into the space at one time. So we practiced in halves, which worked out well, as one half could then critique the other half, each girl giving the person they were assigned to feedback about doing the moves correctly or moving in unison with the rest.

My first year on the squad, I piped up a bit too much in giving feedback to girls who were a year or two older than me. God bless Stacy, my friend who was one year ahead of me, for taking me aside and letting me know I was getting on people’s nerves. I needed to back off, she said, and so I did. For the rest of that year and all through the next, I kept my head down and focused on my own performance, whittling my comments down to only those that really mattered.

Every year, there had always been two co-captains, elected by the squad in the spring of the preceding year. In our junior year, when we showed up to vote for the next year’s leadership, the current co-captains informed us that instead of voting for two girls this time, we were only voting for one. There would be a captain the next year, and she would have a co-captain. I had not seen it coming that I would walk out of that meeting elected captain, with Laurie as my co-captain.

During the winter basketball season, it was imperative we practice in the gym a few times before each performance so the whole squad could do the routine together. Plus, we used markings on the gym floor to spot our positions, and we needed to find our marks and rehearse using them. Gym space was at a premium, with the basketball team using it every day after school, so we got floor time in the mornings before school started.

Walking to school for a 6:45am one-hour practice—we had to allow time to shower afterward and do our hair—in below-zero temperatures was never much fun. Worse, we followed a fashion trend of wearing leather-soled moccasins to school, even in the winter, so our shoes and socks were soggy most of the day.

The year I was captain, for some unknown reason—unseasonably warm weather perhaps?—I got word one day that we could have the gym after school that week. The basketball team would be practicing outside. The heavens had shined upon us.

But as we were practicing, the heavens must have changed their mind because the sky opened up and started pouring rain. Within minutes, the boys came pouring into the gym. “Get out!” they were yelling. “We need to be in here!”

Before I could turn around, my co-captain Laurie lit back into them, yelling that we had been given the space and they needed to get the hell out so we could practice. It was quickly apparent, though, that we wouldn’t win this battle, so I grabbed Laurie and off we all slunk. The next day, while sitting in class, an announcement came over the PA system requesting certain students report to the classroom of Mr. Olsen, the football coach. Next, the school secretary read off the 18 names of every girl on our pom-pom squad. Oh dear. We were in trouble.

Part of the problem was the yelling. Laurie’s fuse had been lit and she had really gone off on them, including the coaches. The bigger problem, however, was that we didn’t seem to know our place. The coach hated he had to say it, he said, “but girls, you’re just not as important as the boys. For if there was no basketball team, there’d be no Warriorettes.”

What do you say to that? For the logic is compelling. And yet this is the fundamental reason that a federal civil rights law known as Title IX had been enacted in 1972, requiring equal treatment for girls and boys in sports. Otherwise, as long as Friday nights and Saturday afternoons—the prime times for spectator sports—continue to be dominated by boy’s football and basketball games, female students would continue to take a backseat. This law has since gained far more traction than it had at the time.

Another notable occurrence from that day-and-age was when the pom-pom squad decorated the gym for the Sadie-Hawkins (girls ask boys) dance. The tradition was to tape crepe paper streamers to the center of the gym ceiling and then fan them out to where they were taped around the edges of the room. It made for a nice effect but required a handful of high school girls to climb on top of scaffolding—kindly provided for us by the janitor—in the center of the hardwood gym floor.

Going up the ladder was OK, but climbing up and over the top edge was scary. A few of us would sit up there taping streamers to the scoreboard. Then we’d drop the crepe paper spool down for someone to catch-twist-and-tape before throwing it back up for us to catch. We had to be careful not to lean out too far to grab a bad throw and thereby potentially topple over the side. And let’s face it, there were a lot of bad throws.

Next Chapter

Return to Walker Contents