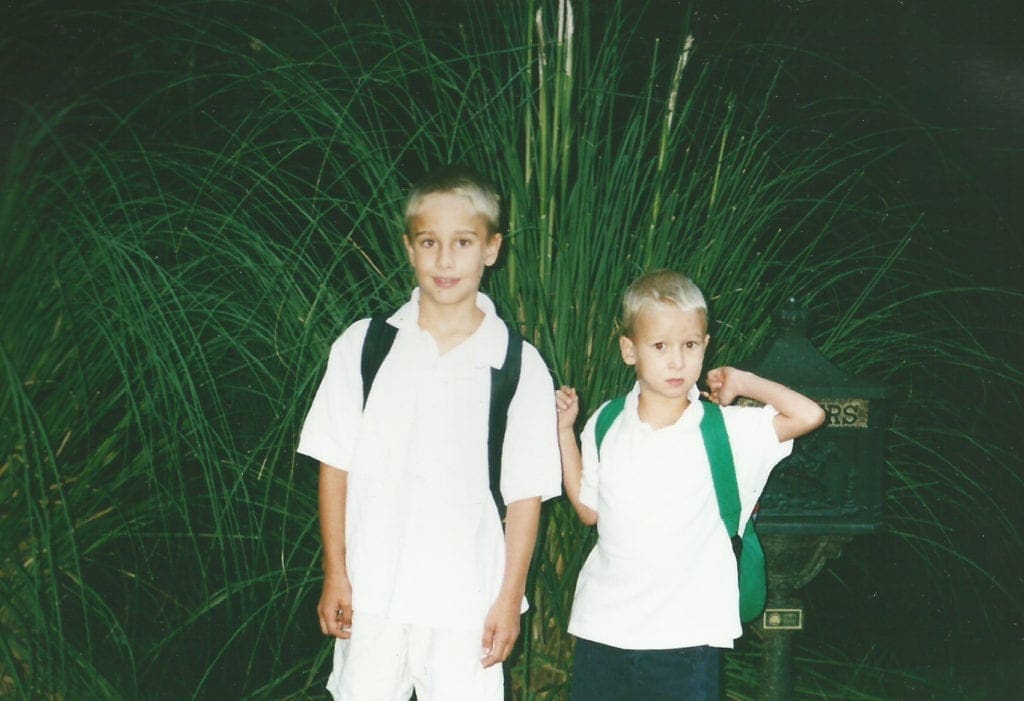

In the early 2000s, the boys were in their formative years of just learning to read. At my friend Melinda’s suggestion—she also had two boys—I picked up the first Harry Potter book and read it to my boys while they were in the bathtub. Same with the second book in the series, although by then it had also become bedtime reading. The third book we listened to as an audiobook—book-on-tape, back then—while driving to Delaware to visit Rick’s mom.

By then, the boys were starting to read on their own and I dropped out. By the time the seven-book series finished unfolding, Rick was taking them to stand in line at Barnes & Noble at midnight to get their copies, hot off the press. Of course, both boys would need their own hardbacks, the irony of which is that one or both of them would finish reading it within 24 hours.

Over the years, both boys have been voracious readers. I credit their reading speed, in part, to their also having hit the stride of Pokémon and Game Boy devices just right. Pokémon cards were huge when the boys were little, with merchandizing that included TV shows and videos, posters, and stuffed animals that turned inside out to morph into one of their other forms. This was right when the first Game Boy Color came out, and the boys were consumed with playing Pokémon on it. Doing so meant they needed to read text onscreen quickly, which I think their malleable little brains figured out how to do on the fly.

As they got older, I more than once complained about how the boys tore through so many series of books, I was then forced to pay full boat for the hardcovers when the next in the series came out. I know, rough life. In truth, it sometimes seemed they read too much. It also seemed they played their Game Boys too much—listening to them kibitz in the back seat playing Pokémon with their Game Boys connected to each other was like listening to people speaking a foreign language—and yet we supported the habit, cycling our way through each new iteration: Game Boy Advance, Game Boy Advance SP, Game Boy DX, and on and on.

They also played a lot of sports. Soccer kicked off for both at age four, and the neighborhood swim team started at age five (they had to be able to swim one length of the pool on their own). Over the ensuing years, they each went on to participate in some combination of baseball, basketball, karate, tennis, lacrosse, golf and water polo. In the end, both boys received the rare acknowledgement at graduation for having played three sports during high school. In both of their classes, only one other student had done the same.

And clearly, they were also attending to their schoolwork. Charlie would go on to become a gainfully employed engineer living in California, where he added beach volleyball to his list of sports. And Jackson is knocking it out of the park in veterinary school. So for the most part, both boys were straight-A students all the way through.

In fact, when Charlie was in fifth grade, I attended a workshop at his school in which we were encouraged to let our straight-A kids know it would be OK to get a B, and preferably sooner than later.

“If they get all the way to high school without getting a B, it’s going to hit them really hard to get their first one there,” the school counselor explained. “And Lord help them if they get their first B in college. That would be devastating.”

Maybe Jackson overheard my conversation with Charlie, or maybe he just decided to find the edge while still in grade school by seeing how far he could go before he landed in B territory. He found it, with three of them.

“If that’s you doing your best, Jackson, good for you. If you can do better though, you should try,” I said.

Toward the end of the semester, I heard Charlie mutter a nickname at Jackson in the back seat.

“What did you just call your brother?” I asked.

Charlie said nothing.

“He’s been calling me 3Bs since we got our last report card,” Jackson said.

There’s nothing quite like that brotherly love.

At work, over the same five years starting in 2000, I would wind my way through various marketing manager roles, traveling internationally and writing more marketing strategy documents than you can shake a stick at. I was personally active, in various ways and to various degrees, in fiber optics, electronic connectors, LEDs, aircraft components and mobile phone housings. At one point, I even took on sales responsibilities in the mobile phone area to make myself more useful. I found the work to be both challenging and satisfying in many ways.

Amidst all that, a few important things happened. First, in 2001, Rick and I split up. We’d started couples counseling several years prior and despite our good intentions, nothing was changing. We were two withdrawn people who couldn’t find a way to connect. Fortunately, through all that, we did well as parents. But as partners in an intimate relationship, we were dismal.

Things came apart at the seams right around the time the Twin Towers in New York were taken down by terrorists. ‘The twin towers in my kids’ lives are about to come down,’ I’d thought, ‘And they don’t see it coming either.’ I was filled with sadness. I couldn’t fix our marriage, I couldn’t stay in one so broken, and I couldn’t bear how much this would hurt my little boys. It still brings tears to my eyes.

For all my shortcomings, I put everything I had into making life as seamless for the boys as I knew how. For one thing, I managed to stay in the house, renting out the lower level for several years to make ends meet (the boys got the master bedroom again and I moved my bedroom into the loft). My dad came down for a week and helped convert the downstairs shop into a kitchen. When he left, he handed me a check for $150.

“What’s this for?” I asked.

“Go buy yourself some decent tools,” he said.

Rick rented a house in the same neighborhood. We actually had adjoining property lines through the woods. (“Kids, we forgot your winter coats at Dad’s yesterday when I picked you up. Finish your cereal; I’ll be right back.”) The dog Kelsey went with Rick, who always had way more patience with her than I did, and I kept our cat Blue. When I traveled, Blue figured out to show up at Rick’s house instead of mine. Best. Cat. Ever.

Two years later, in 2003, I would begin training to become a Pathwork Helper. This was a four-year program that involved a weekend a month in Atlanta plus several weekends a year in New York, along with one Pathwork retreat a year led by a senior Helper, in addition to leading a monthly lecture study. All that was required on top of having individual one-hour sessions with a Helper twice a month.

For our fourth year, we also joined a group at Sevenoaks for four four-day weekends. Our class in Atlanta had shrunk, and it was the year we were studying how the body develops in response to childhood trauma. Having 17 bodies to look at was way better than two.

Before I had gotten divorced, Rick and I didn’t keep close track of our expenses. As long as the checkbook kept balancing and staying in the black, we felt we were OK. After, it was mission-critical that I knew where all my pennies went. One key consideration for starting down the road to becoming a Helper was the expense. It ended up costing several thousand more than I had anticipated, and I never thought it likely that I would recover my investment by leading groups and giving sessions.

But that was OK for me. I had a day-job and the amount of personal growth I was getting out of the training made it worth it to me. More than that, I discovered something that was invaluable. This felt like the right next step for me, and so I believed the money would be there to cover it. And it was. The spirit world had my back.

Over the coming year, my attendance at AA meetings would dwindle. Mostly, I just couldn’t keep all the plates spinning. I eventually landed squarely on this AA saying: “My sobriety is contingent on the daily maintenance of my spiritual condition.” I had spirituality out the wazoo through the Pathwork, so after 15 years of attending regular AA meetings, I stopped going. Of course, I also knew that if I ever found myself on slippery ground, I’d know exactly what to do to get back on firm footing.

It was unfortunate timing that after serving for several years on my neighborhood’s homeowner’s association board, it was my turn to be president in the midst of everything else going on. This was something I’d put off once already due to workload, but two years prior when asked to be vice president, I had agreed. Now I was in the bucket. As luck would have it, early that year a developer bought six lots on the edge of our neighborhood, looking to tear down the houses and put up cluster homes. Many meetings later while sitting together in my living room, we’d worked out an agreement we all could live with.

On the heels of that, I was informed that a nearby school had bought 69 acres of land adjacent to our neighborhood, impacting 13 neighbors. Something similar had occurred not far from us, and one of the opposing neighborhood moms had decided to make a living fighting these kinds of “invasions.” She was stoking a fire under our affected neighbors and fixing to make a real stink. To avert a disaster, I contacted that other school and got a download on what a good endgame looked like. Then I painstakingly walked both sides—the school and the impacted neighbors—through a negotiation that ended in a peaceful, harmonious agreement.

When the boys were in high school, I would step up to be the president of the band boosters. Having grown up surrounded by music, I loved being around the band kids; there are few things that make my heart sing like a good drum cadence. I had already been volunteering for a few years to get the uniforms in and out of the closet before and after games, when the slot for president opened up. Honestly, I hadn’t volunteered at the boys’ schools much before that. Some bandwidth had freed up after Pathwork Helpership training finished, and since I’m pretty good at leading things like this, I raised my hand.

The boys were in the band together when Jackson was a freshman and Charlie was a senior. They both played French horn, meaning they played mellophone in marching band—the bell on a French horn faces backward, and marching bands are all about projecting sound—and Charlie was the section leader his senior year. So he was both Big Man on Campus and Boss of Little Brother.

In the spring of 2011, after I had already been band booster president for a few years, I was sitting next to Jackson in the high school auditorium for the senior awards ceremony when I heard Jackson tell his friend he didn’t think he would do marching band again in the fall. It conflicted with water polo and he really loved playing water polo. Beg pardon?

“Jackson, if you’re not going to be in the band, I need to know, because I’m sure not going to be the band booster president with no kid in the band!” I said. A mad scramble ensued. We were sprinting toward the end of the school year and I needed to find a replacement fast.

The good news was, I found someone. The bad news was Mary was only willing to do it if I would swap with her and become the treasurer for the Friends of Math & Science. I agreed. I had been judging their science project competition ever since Charlie was a freshman, and I loved the weekend-long math competition they sponsored, called CO-MAP, so I supported their cause.

That evening at the awards ceremony, Charlie shook hands with Georgia Senator Judson Hill, because he was the STAR Student, the senior with the highest SAT score. That weekend, he also shook the hand of famous UGA football coach Vince Dooley when he won the Spartan Scholar Athlete award. Charlie may have only applied to one college, but he was a shoo-in.

He was undecided, though, about trying out for marching band at Georgia Tech. I had a conversation with a colleague whose son was in the Georgia Tech band that helped.

“Tryouts aren’t hard,” she said. “Face forward and play loud. Plus the kids get two credits of an easy A—at Georgia Tech!” I told Charlie this and he was all in.

Later, his social life in college would revolve around his marching band activities. He had a blast. Toward the end, he even worked his class schedule in such a way that he could get in one more season with the band. As part of Title IX, both the band fraternity and the band sorority, because they were categorized as service organizations, were required to admit both male and female students. Midway, Charlie received a bid to join TBS, Tau Beta Sigma, the band sorority. So while I may never have had a daughter, now Jackson had a sister!

Next Chapter

Return to Walker Contents