Moving into sixth grade was a big step up into middle school, what with combination lockers and boy/girl dances and all. Janet had been diagnosed the summer before with severe scoliosis and was now wearing a full body brace around the clock. It took a lot of the wind out of her sails. And I met Melinda, who would become my best friend for the years to come.

I remember a girl in class named Gretchen being asked, or perhaps teased, by one of the boys, Bob, about what she wanted to be when she grew up. Gretchen was very bright and I distinctly heard her say, “I am going to be a doctor.” Maybe she had already proclaimed this and that’s why the boys were laughing and teasing her.

In any case, that idea lodged in me like a bullet. For the next eight years, the idea of becoming a doctor seldom left me. In high school, I would flesh it out further to wanting to become a plastic surgeon. I had no thoughts of performing facelifts but liked the idea of reconstructing people who needed to be put back together.

During the course of my sixth year in school, my father’s drinking would devolve until the bottom was found. Or at least a first bottom. One of my mother’s co-workers said to her, “You have to do something. I was out with Ed last night.” When other people see the problem, well, that’s where the rubber meets the road.

A few years prior, we had bought a plot of land on a tiny lake called Slim Creek—so quite literally, just a dammed up creek—40 minutes north of us, and parked the camper there. I was destroyed the day I watched my dad take the wheels off the camper and put it on cement blocks. We really weren’t ever going to go camping at a campground again. The lot was remote with just one family we knew nearby for company. One night, after Dad got drunk, the rest of us cowered inside the camper while he threw gasoline on the fire. Let the good times roll.

By my sixth year in school, that lot had been sold in favor of a cabin. It was a cute little place 20 miles north of us on Big Devil’s Lake. No running water—you had to pump water into a five-gallon jug at the bottom of a fairly long, steep hill—and so no indoor toilets. Our friend’s cabin had a two-holer, but we had a one-holer outhouse at the cabin. (I still think “one-holer” when I walk into a public restroom with just one toilet.) I wrote this poem and tacked it inside the outhouse door for reading entertainment.

An outhouse is to make you gladder.

It also helps relieve your bladder.

It stinks a bit, as they all do,

But keep in mind it’s full of pooh.

But folks please do remember,

This is no deluxe suite.

It’s only meant for folks like us

To do our twinkie-tweet.

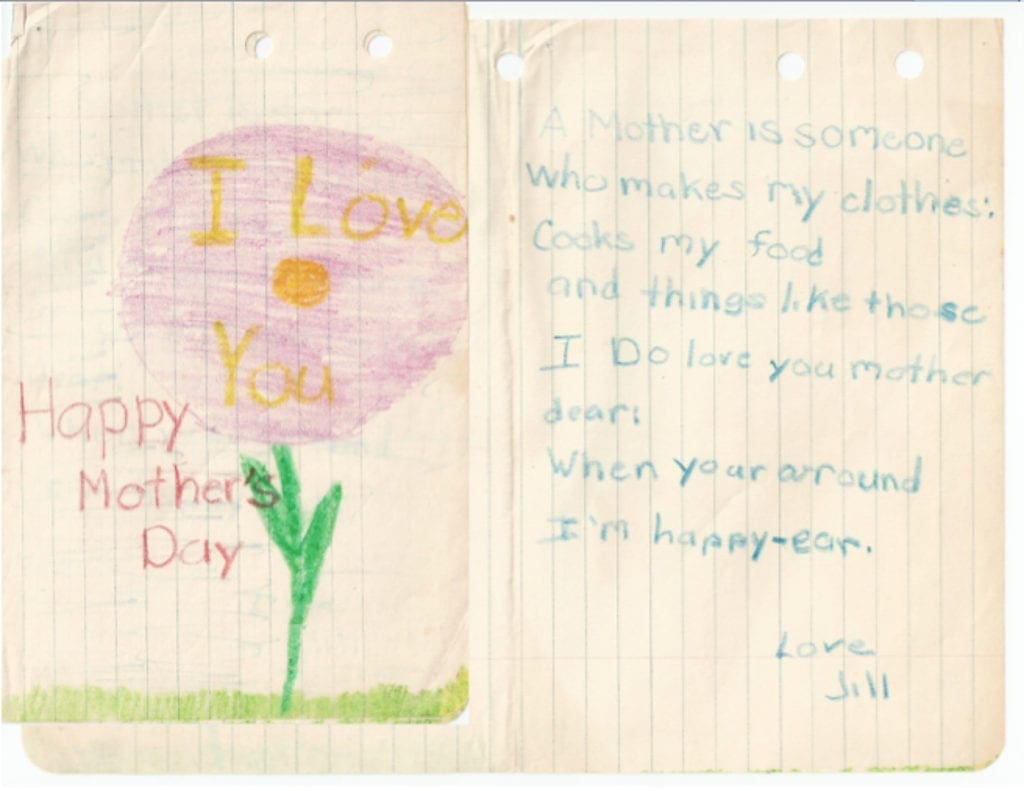

It seems I had a problem with changing the cadence halfway through a poem in my early works. So I’m guessing the saved Happy Mother’s Day card I made for my mom is the same vintage. The poem inside went like this:

A Mother is someone

Who makes my clothes;

Cooks my food

And things like those.

I do love you

Mother dear;

When your around

I’m happy-ear.

Years later, when Pete got married not long out of high school, he and his pregnant wife would live in the cabin. My dad and brothers had spent quite a bit of time together fixing the place up—fondly referred to as Thompson and Thompson Construction—and for the occasion had winterized it and added indoor plumbing.

Sarah was born in October of 1978, and a week later I was babysitting her so Pete and Mary could go out for Mary’s birthday. At one point, Sarah began to cry with gusto and I, being only 15, was a bit out of my depth. I was also torn between talking with her as I rocked her and not talking. I was totally confused about whether babies might prefer total silence. Eventually she calmed down and fell asleep.

Our family did have some good times up there at the cabin. For example, we had a huge antenna on the roof that took three people to adjust: One to stand on the roof and turn, one to stand outside and give directions to the person on the roof, and one to stand inside and yell when the picture was clear. Or clear enough.

This was the early days of Saturday Night Live, and we discovered all those hilarious legends—Loraine Newman, Chevy Chase, Jane Curtain, Dan Aykroyd, Lily Tomlin, John Belushi—while laughing together until our sides ached. Mom typically made a pan of bars for the weekend—a cake pan layered with sugary goodness cut squarely into treats—and we’d have a case of grape, orange, cola and lemon-lime pop from the Holiday gas station. Sometimes we’d get Jolly Good pop—that’s soda, for the rest of the world—that had jokes inside the bottom of the can.

But good times were few and far between. Fortunately, my mother had started getting counseling and support from Reverend Carlson, a Methodist clergyman who had some experience working in a treatment center. So in February of 1975, they planned an intervention to get my dad into treatment for alcoholism.

By the end of what my mother calls “one of the longest weeks of my life,” my dad agreed to go off to a 30-day program, but not until the end of the school semester.Because, what would people think if they found out? For the next three months, the drinking got worse and the fighting got louder. It would start up late at night, not long after I heard the garage door go up. Here we go again. Dad’s home from the bar.

I recall during class, the teacher putting on a film and then turning off the lights. I put my head on the desk and fell asleep. The fighting at nights took a toll on everyone. The teacher came and asked if I was OK. Of course I was not, but I said, “Yes, I am fine.”

For some reason, perhaps for a class assignment, I had written this poem that was particularly depressing:

Looking out the window

Watching people pass on by,

Looking all so lonely

Gee, I wonder why.

No one stops to say hello

Or offer a friendly smile,

To make their day more cheerful

Or to make their day worthwhile.

Just push and shove to get on home,

To end their day at last.

To greet their house like a (something, I forget)

Another day in the past.

Not surprising, this triggered my spending extra time with a teacher before school. Perhaps she’d been told about my dad going to treatment? I felt she was trying to help, but I wasn’t clear with what. She turned me onto Nancy Drew books, which I appreciated as a way to escape, but more words of explanation would have been more helpful.

Years later, I would send one of my own kids to a school counselor following my divorce. Charlie later said he was clear the woman was trying to help him but wasn’t clear what the problem was. He couldn’t make the connection between why a school counselor would be talking with him about home things. This was his sad poem, written about four years after our divorce:

My Life, by Charlie Sanders, circa 2005 (~age 12)

My life is like a typhoon

Only calm in the middle,

Everything ends too soon,

It’s all so big, and I’m so little.

In the middle of the day, I feel at home

Cause I’m always on top of things.

But in the mornings and at night,

I always feel alone.

One more thing to top it off,

Making this poem great.

I’ll always love my family even

If they’re not first-rate. (Seriously)

Charlie agrees that for him, middle school was a mixed bag. And although he recalls being lonely at times, he wouldn’t hang all of that on the divorce. He remembers that there were bright spots too.

We also had a bit of a bright spot in my family, albeit in the midst of a very cloudy patch. Between the time of the intervention in February of 1975 (which I hadn’t been part of but knew about) and the start of treatment at the end of May, our family was selected by an area organization—the Rotary Club perhaps—as the Music Family of the Year. A picture of our smiling family, complete with our dog Maggie, was taken for the Chronotype, the local newspaper. As my father shipped off for what would be the first of many visits to Hazelden, one of the greatest concerns in my 11-year-old head was we’d be stripped of the award.

Next Chapter

Return to Walker Contents