From what I understand, the complexion of this homogenous white-bread area has changed quite a bit in recent decades, owing to the availability of jobs at the turkey plant which support so many families in the region. Asians, Hispanics and Africans—including refugees from the civil war in Somalia—are now all part of what makes up the little burg of Barron. For me, until I got to college, I had only white kids for classmates.

Racism, in hindsight, is something that can lie dormant in the soul, only surfacing when something comes along to wake it up. Growing up, though, it seemed a non-issue in my life. When everyone you live around has essentially the same color skin, it just never comes up.

It’s interesting to realize, then, that when I got into high school, living in a farming community as we were, the students developed their own version of “racism.” It was the farmers vs. the jocks. The farmers wore a special jacket—a navy blue jean jacket made of a velvety soft material—emblazoned with their name and the Future Farmers of America (FFA) logo. The jocks had their letter jackets. Personally, I still have my letter sweater.

One year, when I was a junior or senior in high school, the farmers had had their fill of watching perky cheerleaders and strapping football or basketball players walk off with the crowns at prom. So they devised a catchy chant for their prom queen choice: “Debbie Prock, Debbie Prock, she’s a farmer, not a jock.” Repeat it over and over, loudly, at the pep rally, and you can guess who our queen was that year.

It’s entirely possible Debbie Prock was the most deserving person in our school to be elected queen. Or maybe she just had the best name for a chant. I was on the pom-pom squad, so I didn’t run in her circles. Actually, I wasn’t in her grade, and with 200 or so kids in each class, it’s not a complete surprise I had never heard of her.

The point is, there was division and there was tension. I don’t recall any physical fights, although there probably were some, and I didn’t have any angst of my own in this battle. But later in life, I would need to take a good hard look at how fractures of “us-versus-them” lived in me, even though I was raised in a part of the world where we really did sing Kumbaya around a campfire. More than once.

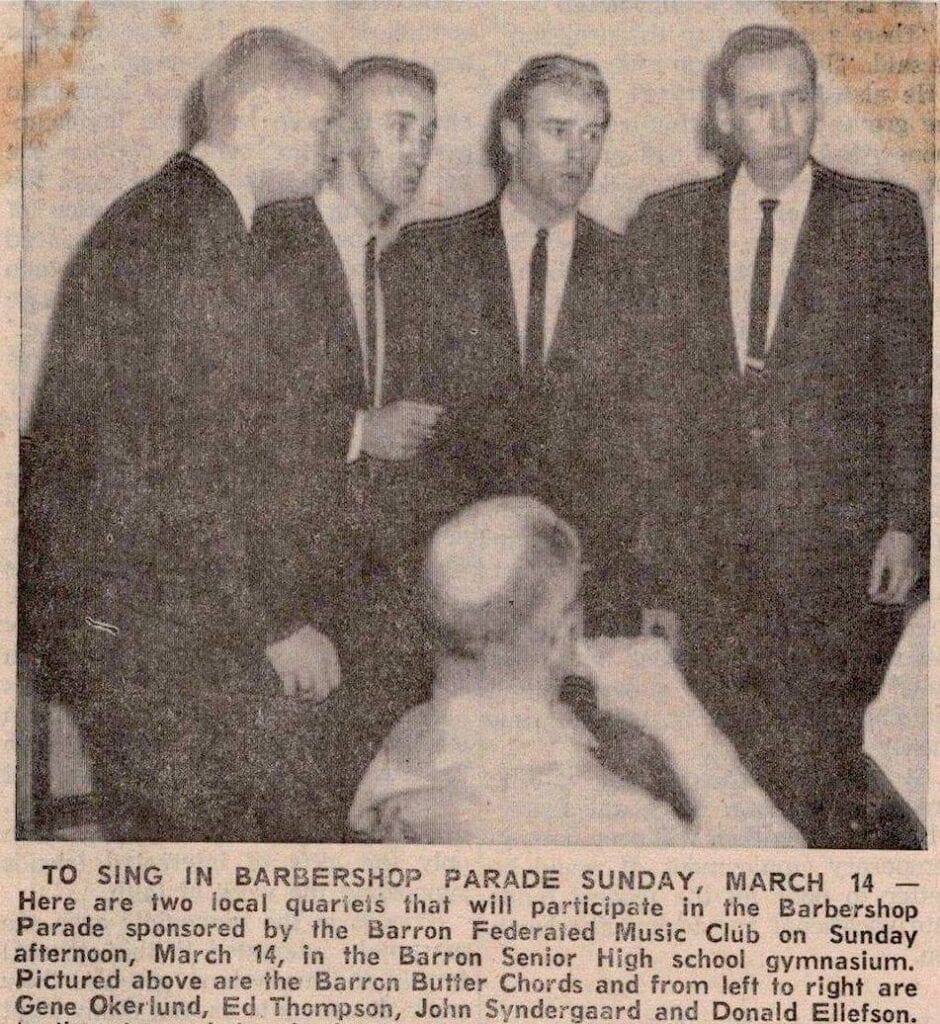

While we lived in Barron, my parents were active singers in the Lutheran church choir, with my dad the choir director. My dad also sang bass in a barbershop quartet. Once a year, there was a barbershop choir concert, featuring numerous quartets and including at least one “big act” that came in from another region and sold their records during intermission. I still have one of them and if I still owned a record player, it could make for some fine entertainment.

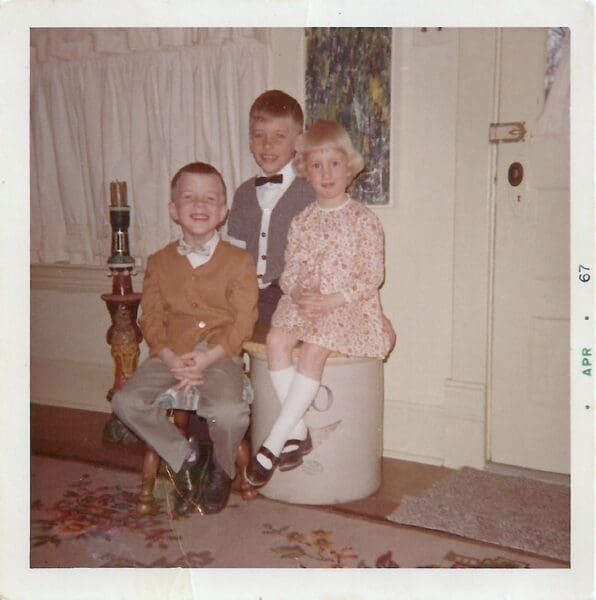

One year, all the children of the barbershop-singing dads were gathered into a choir and led onto the stage to sing the closing song, God Bless America. I was taken to rehearsals but didn’t understand what we were doing. This is my earliest recollection of the impact of, by and large, not being spoken to as a child. As I was being dressed for the concert, most likely done up using curlers in my hair, I still didn’t know where we were going or what we were doing. Walking up on stage, puzzle pieces starting falling together. Oh, this is what we’re doing. I just remember thinking, “Did everyone else know this was the plan?”

The quartet my dad sang in was called the Butterchords, and they were quite good. John was lead, Don was tenor, Jim was baritone, and my dad sang bass. My dad arranged many of their songs and they practiced quite a lot. While never big-time, they did actually make a record, recording at least some of it in our living room.

When all of our families went camping together, the quartet would gather around the fire and the entire campground would show up for the free concert. My favorite songs of theirs included Daddy Sang Bass, Just Looking and The Preacher and the Bear. Over time, barbershop singing has disbanded and the world has lost something that was endearing and more than a little special.

At Christmastime, our family joined with other families to go caroling in old folks homes. As a kid, I found the smell of those places hard to take, and seeing the aging people without all their faculties wasn’t easy. But I can now see that we were offering a gift that not many have experienced either giving or receiving. Even today, now into his 80’s, my dad regularly plays tuba with a group of big-hearted men and women who offer live music to people in senior citizen’s centers not far from where I grew up. This is a charity that is far more valuable than money and is most assuredly being gratefully received.

The other musical group that my dad formed and which endured for many decades was called We3. My dad sang bass and played the bass fiddle, Jim Sockness sang and played the tambourine and kazoo, and Don Ruedy sang and played the guitar and banjo. They would dress in matching outfits, back when white shoes and a white belt were in style, and I thought they were awesome. Their genre was folk music, and among my favorites was Lizzy Borden.

Lizzy Borden took an ax

And gave her mother forty whacks

And when the job was nicely done

She gave her father forty-one

Yesterday in old Fall River, Mr. Andrew Borden died

And he got his daughter Lizzie on a charge of homicide

Some folks say she didn’t do it, and others say of course she did

But they all agree Miss Lizzie was a problem kind of kid

‘Cause you can’t chop your poppa up in Massachusetts

Not even if it’s planned as a surprise

No you can’t chop your poppa up in Massachusetts

You know how neighbors love to criticize

She got him on the sofa where he’d gone to take a snooze

And I hope he went to heaven ’cause he wasn’t wearing shoes

Lizzie kind of rearranged him with a hatchet so they say

And then she got her mother in that same old-fashioned way

But you can’t chop your momma up in Massachusetts

Not even if you’re tired of her cuisine

No, you can’t chop your momma up in Massachusetts

You know it’s almost sure to cause a scene

Well, they really kept her hoppin’ on that busy afternoon

With both down and upstairs chopping while she hummed a rag-time tune

They really made her hustle and when all was said and done

She’d removed her mother’s bustle when she wasn’t wearing one

Oh you can’t chop your momma up in Massachusetts

And then blame all the damage on the mice

No you can’t chop your momma up in Massachusetts

That kind of thing just isn’t very nice

Now it wasn’t done for pleasure and it wasn’t done for spite

And it wasn’t done because the lady wasn’t very bright

She’d always done the slightest thing that mom or pop had bid

They said, “Lizzie cut it out!” so that’s exactly what she did

But you can’t chop your poppa up in Massachusetts

And then get dressed and go out for a walk

No, you can’t chop your poppa up in Massachusetts

Massachusetts is a far cry from New York

No, you can’t chop your poppa up in Massachusetts

Shut the door and lock and latch it

Here comes Lizzie with a brand new hatchet

You can’t chop your poppa up in Massachusetts

Such a snob I heard it said

She met her pa and cut him dead

You can’t chop your poppa up in Massachusetts

Jump like a fish, jump like a porpoise

All join in in a habeas corpus

No, you can’t chop your poppa up in Massachusetts

Massachusetts is a far cry from New York!

Next Chapter

Return to Walker Contents